“But here is a situation where we’re not living up to our best selves.”

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-tbt.s3.amazonaws.com/public/FV6YH7WKGEI6TODGIBWI6S7HAY.jpg)

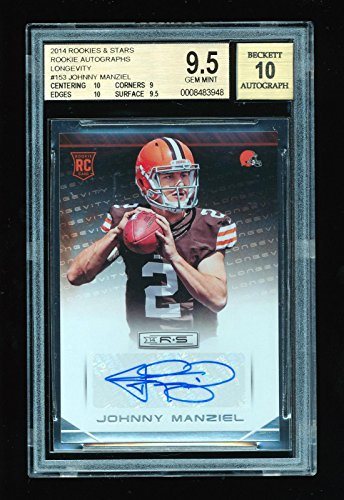

“Universities are quick to lecture society,” says Charles Clotfelter, an economics and public-policy professor at Duke University and the author of the probing 2011 book Big-Time Sports in American Universities. According to a 2012 study from Oxford Economics, a global research firm, a season’s worth of Texas A&M home football games generate $86 million in business for Brazos County, where A&M is located.īut the players with the talent remain out of the money simply because a group of college presidents, athletic directors and conference commissioners set their wages at zero. Souvenir hawkers, bars, burger joints, hotels, ticket brokers, stadium vendors, parking attendants and others rely on home games for revenue. Football-game days in particular drive college-town economies. Coaches, admissions offices and university alumni operations profit from the stars.Īll kinds of people beyond campus are also making money from this lopsided system. Thanks to plush television-rights deals, like the 12-year, $3 billion contract the Pacific-12 conference signed with ESPN and Fox in 2011, vast revenues will keep rolling into university coffers. The uncomfortable question has surfaced just as college sports are booming. Manziel is surely worth a great deal more. Why shouldn’t a player worth so much to his school, to his town and to the college-football brand be able to sign his name for money, just as any other celebrity has a right to do? How much longer can everyone else make money from college athletes like Manziel while the athletes themselves see their cash compensation capped–at $0? According to a recent study, if college football operated under the same revenue-sharing model as the NFL, each of the 85 scholarship football players on the Aggies squad could see a paycheck of about $225,000 per year. Manziel’s alleged crime and televised punishment have teed up a debate that has been simmering for decades but is now more intense than ever. He mimicked signing an autograph while jawing with an opponent and pointed toward the scoreboard in the fourth quarter, earning an unsportsmanlike-conduct penalty and another benching, this time from his coach. He threw for three touchdown passes in the second half of A&M’s 52-31 blowout victory over the Owls in front of almost 87,000 fans at Kyle Field in College Station, Texas. Like most college-sports critics, Manziel responded to this punishment by mocking it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)